This site is an archive of documents and images as well as other information relevant to the history of climbing in Australia and Australians climbing overseas from the late 1960’s drawn mainly from my experiences in the European Alps, Africa and North America. Comments are welcome. (rockofageskb@gmail.com). Text © Keith Bell 2018.

Refer also to htpps://talesofpro.blogspot.com

Copyright to photographs is held by the named photographers. Photographs by the author will be titled only but copyright still applies. Other photographs taken on the author’s camera by an unknown person will be credited to the Keith Bell Collection (KBC). Please request permission to reproduce.

FOREWORD

Keith Bell is a pioneering Australian climber and his unwavering enthusiasm, intensity and love of the heights are evident in the following pages. There is arguably no other Australian climber who can match his extraordinary ascent portfolio, spread over five decades. His passion for climbing is as strong today as it was when he took his first tentative (and barefoot) steps into the vertical world in the Blue Mountains in 1962. As recently as 2017, he made his third ascent of Balls Pyramid as a climbing guide for an Australian Museum expedition seeking the Lord Howe stick insect, long believed to be extinct until rediscovered by climber Dave Roots in 1964. Keith’s extraordinary drive, coupled with his high level skills as a rockclimber and alpinist, have seen him complete countless new routes (and memorable repeats) on several continents, including his homeland here in Australia.

Another aspect that sets Keith apart from others who have followed in his footsteps are his stories of the varied exploits that have shaped his climbing life, written and published along the way. Despite being the lone Australian in Chamonix in 1970, his first Alpine season saw him claim first Australian ascents of routes many of us who were climbers at that time had only read about — and dismissed as well beyond our capabilities: the Gervasutti Pillar on Mont Blanc du Tacul; the South face of the Aiguille du Midi — and half a dozen others. In subsequent seasons in the Alps, he teamed up with Australian climbers, Howard Bevan and John Fantini, experiencing terrifying classics like the Walker Spur and the North face of the Dru. Reading Keith’s vivid and engaging accounts of these legendary routes somehow makes them seem more real because they are part of Australian climbing history. In between these Alpine seasons, he travelled to Africa, reaching its two highest summits — Kilimanjaro and Kenya — and leaving behind a swag of new routes on the sandstones of Towerkop in South Africa’s Western Cape.

Not content with tilting at thunderstorms and blizzards in the Alps, Keith’s adventures took him across countless foreign borders in various motor vehicles of doubtful roadworthiness and legality under the control of climbers with questionable driving skills! In 1973 he was in Yosemite where he made the second Australian ascent of The Nose with the legendary Henry Barber, missing out on making the first Aussie ascent with Rick White by only days after being offloaded from his flight en route from Sydney. In typical style, Rick waited for no one — even old mates! But Keith moved beyond the Valley, leaving a legacy of new routes in an extraordinary climbing odyssey through the Sierra Nevada, Colorado and Wyoming.

And then there were the Blue Mountains and the Warrumbungles where he and various partners — including the inimitable Humzoo (Ian Thomas) and Ray Lassman — climbed some of the most memorable challenging, run-out multipitch routes in the country on the intimidating, steep trachyte walls. His account of the classic, Flight of the Phoenix, on Bluff Mountain is a gem. Ray climbed with Keith on that first ascent and rates this route as the best he has done — anywhere in the world!

So all this — and more — is in store in the pages that follow. Keith’s accessible style takes us into the eye of the storm — and shares with us the joy of reaching yet another summit, wherever it may be. This diverse collection confirms his place as a pre-eminent figure — as both a climber and a writer — in Australian climbing history.

Michael Meadows July 2018

Starting out.

Early barefoot climbing experiences in the early 1960's at Wahroonga Rocks - Northern Sydney.

(KBC)

INTRODUCTION

The genesis of this work can be attributed to a recent conversation with a good climbing friend when in a conversation he said:

“You know, I really enjoy reading your climbing articles, you should dig them out and put them into a book”.

At first I was not enamoured with this suggestion. Having already made a foray into the climbing book domain I had come to the conclusion that it was a ‘mug’s game’. He had, however, lit a spark and when I mentioned this to some other good friends their suggestion was to create a Blog. After ruminating on this for a while, I gingerly started digging the offending articles from the archives (*). Apart from the articles though, their retrieval also elicited a flood of memories. Before I knew it I had started trawling through boxes of climbing slides that had lain dormant for decades and unexpectedly I was hooked. Suddenly I needed a name.

Rock of Ages came to mind. Being a rockclimber I thought that the spiritual rather than religious element of this name might resonate along with the seemingly timeless and infinite nature of the medium that we climb on. I thought that it also considered the fact that we all have predecessors who have built the scaffold on which contemporary climbing in all its variants owes its existence. But climbing is many things: the trip to the rock, access, the climb, descent, the trip home, success, failure, the weather, objective dangers and most importantly, our fellow travellers. I see climbing as a holistic endeavour where the rock and climbing, although central, is not the complete story but is the stimulus for the entire journey. I hope that this is conveyed in what follows.

(*) All articles have been fully referenced below the title. The headings of recollections are printed in underlined italics.

|

Early days on the Second Sister - Katoomba with NZ friend, Tony Hartnett. (KBC)

|

HEIGHTS & DISTANCES

Metric and Imperial measurements have been used in the following articles and have been left as written at the time.

12 inches = 1 Foot

1 Foot = 300mm

3 Feet = 1 Yard

1 Yard is approximately 1 Metre

CONTENTS:

I) Getting Ready

A. BREAD and CIRCUSES:

A1. A Terrible Tangle – What not to do with a 400 metre rope.

A2. Tales from the Crypt - Rope Dope

A3. Start the Ball Game.

B. HAVING A BALL: 1970, 1973 and 2017

B1. 1970 Balls Pyramid Expedition Report

B2. Balls Pyramid – 1973

B3. Australian Museum Balls Pyramid Expedition - 2017

C. ALPINE ANTICS: 1970 -1971

C1. Flying High

C2. Chamonix I

C3. And Then There Were Two!! An Alpine Initiation??

C4. All Quiet on the Southern Front or The Storming of the Midi

C5. The Thin Red Line

C6. Oranges and Ice Cream

C7. UK Bound

C8. Chamonix II

C9. A Grand Nightcap – 1971

C10. Just Walkering

C11. The Dru Derby

C12. FOU Man Do or Don’t? – Foiled Again!

C13. Other Routes Climbed – Mt Blanc Massif

C14. Nuts to You, or How to do a Squirrel – 1971

C15. Cutting Loose and Heading North

C16. London To Africa Via Egypt

D. AFRICAN SAFARI:

D1. Getting There

D2. TOWERKOP – South Africa

D3. Animals

D4. The Milk of Human Kindness

D5. Beitbridge Bites Back

E. STATESIDE – 1973:

E1. Consolidation

E2. Coming To America

E3. The Nose of El Capitan

E4. Other Routes Climbed – Yosemite

E5. Europe or the USA???

E6. A Spin or More Over the Sierras

E7. Deadly Rattles and Ursine Activities

E8. Sierra Nevada Routes and New Route – 1973

E9. Rocky Mountain Routes and New Route – 1973 – Colorado

E10. ‘Staggering’ Up The Durrance

E11. Our American Alliance?

E12. Pictorials of some American routes climbed in 1973

E13. More Recent USA Climbs – 2012

F. IN THE BLUIES:

F1. Fragments: Telstar

F2. Echoes of Darkness

F3. Zac the Interloper

F4. Classic Blue Mountains Trad

F5. Mt Piddington - Mt Vic

F6. Zig Zag - Mt Vic

F7. Ikara Head - Mt Vic

G. BLUFF and BUNGLES:

G1. Brewer’s Droop

G2. Flight of the Phoenix

G3. Bungles Bungles and Other Matters – Some Personal Recollections

G4. Towering Tonduron

G5. Uno Ropo Loco

H. ROAD TRIPS and OTHER PLACES:

H1. Frog Buttress

H2. Booroomba Rocks

H4. Mount Arapiles

H5. Go Climb THE ROCK

H6. Hanging Out On ‘The Coathanger’

I. COMMON CLIMBER ARTICLES

I1. Flakes and Shakes: Flake Crack Revisited

I2. From Yorkshire to Eternity

!3. Sojourn at Dyurrite

I4. Tombstone Territory

I5. Tiptoing Through some Bungles - Quicklink

I6. Quicklink to my Common Climber portfolio of articles.

J. BOOKS

J1. South Pacific Pinnacle: The Exploration of Balls Pyramid

J2. The Red Curtain: Climbing Expedition to Mars 2043

K. DEPARTED FRIENDS:

K1. Ben Sandilands

K2. Pete Giles

K3. Bryden Allen

K

Acknowledgements

1) Getting Ready

Even in primary school I was attracted to climbing and spent a great deal of time on my way home from school climbing trees in Ryde Park, Sydney. There was also a set of Monkey Bars near the swings that I often hung about on. Near the top of the park was a sandstone retaining wall and on the left and right lower wings I often tried out my climbing skills. Between the two was a much higher semi circular wall with a bubbler set in its centre. While I used the bubbler I don’t have any memories of ascending this feature. I certainly had designs on it but was probably saved from damage to the ego and body by the inevitable move to high school, which lay in the other direction from my home. Buffalo Creek and its surrounding bushland were also handy so against strict parental instructions, I often walked home through it. It also provided a theatre for leisure time activities for my brothers and our friends on weekends and holidays.

Throughout the 1950’s and 1960’s perhaps the Scouting Movement presented the main pathway to the outdoors. My brothers and I joined up and were introduced to camping and later on to bushwalking. My first roped climbing experience was on a small outcrop near Camp Crosslands north of Sydney. It was not much but I enjoyed it. For several years the Scouts and then Senior Scouts provided experiences in many outdoor pursuits, bushwalking, caving, canoeing, canyoning and some climbing. Initially I walked in the Royal National Park and Ku-ring-gai but later started doing walks around Katoomba and Kanangra. Somewhere along the line I saw an article in a magazine showing people climbing the Three Sisters in the Blue Mountains. This looked like the real deal and I was terrified, yet intrigued at the same time.

|

Negotiating Templetons Crossing on the Kokoda Trail - New Guinea.

(Howard Bevan) |

I left school after the Leaving Certificate in 1963 and for many years a mix of outdoor activities was pursued. In 1965 a friend, Bobby Gerdes and I planned and completed a trip to the Eastern Arthur Range with the intent of climbing Federation Peak by the Voie Normale. We took the hard way by trekking over Mt Picton then returning the same way after completing the traverse and ascent. The following year I travelled to New Zealand and walked the Nelson Lakes National Park, did some easy climbing and scrambling in the Darrens and after that explored some limestone caves on the West Coast. The next year I teamed up with Howard Bevan. We organized a charter flight into Kokoda and walked back along the trail to Port Moresby. The following year I walked and scrambled in the Cradle Mountain — Lake St Clair reserve with Howard and two others.

Early days on the 'Voie Normale' of Federation Peak, Tasmania in 1965

Lake Geeves way below my feet.

(Bob Gerdes)

But climbing was already taking hold even as I ended my time at school, I had attained the Senior Scout Rockclimbing Badge in 1963 and was made an instructor in August 1966. My thanks goes to the late Rick Jamieson for providing these opportunities as he did for many others still climbing today. By 1968 I found that instructing was too restricting and started to climb for my own ends and at the same time, to try to lift my grades. My feeling is that the long apprenticeship I had undertaken with both pack and rope was to pay dividends as I broke out in 1970. Certainly, the lack of experience and a paucity of equipment available had also played its part in this evolution, as the following will show.

Learning the ropes on the First Sister of the Three Sisters, Katoomba - 1960's style. (KBC)

A1. A Terrible Tangle

What not to do with a 400 metre rope

Rock, No 48, Spring (Oct- Dec), 2001, p. 1.

This article follows on from a eulogy that I gave at Hughie Ward’s Memorial Service. Hughie passed away in February 2001; he was a talented and popular NSW climber. Rather disappointingly, the magazine left out this aspect when the article was published.

Hughie Ward at work on Wrapped Coast in 1969.

I suppose anybody who has climbed for any length of time has some skeletons in the cupboard. By this I mean an incident or decision that took them to the edge in more ways than one. I have a recurring nightmare that dates back to 1969 and it still gives me goose-bumps when I think about it. Ah 69, just by looking at the numbers you can tell it was a good year: full employment, mineral booms, free trips to Vietnam for 19 year olds, Simon and Garfunkel LP’s, and the rock opera Hair was soon to open in Sydney. Hirsute hairstyles were in vogue and while barbers struggled to make a living, the year was especially kind to Sydney climbers.

As 1969 was drawing to a close, the avant-garde artist Christo arrived in town with his penchant for wrapping things. Now, this man thought big — he wanted to wrap Little Bay, if that is not a contradiction in terms. The problem was that Little Bay boasts cliffs of more than 30 metres and is not your run-of-the-mill Christmas or birthday present. Christo had to hire climbers and he was willing to pay $20 a day for their services. At this stage many readers are probably thinking ‘ripped off’, but the average weekly wage was about $40 at the time so this little project was a genuine gold mine.

My Mate Hughie roped me in and halcyon days were spent hanging around on abseil lines firing the occasional Ramset nail powered by a heavy charge into the friable sandstone. Target practice was also on the agenda and we became adept marksman with these bulky pieces of artillery. But a more restful pursuit was to find a secluded ledge near the bottom and bask for a few hours in the sun, absently watching the waves break against the rocks.

Unfortunately, the carefree days and the lurk itself came to an abrupt end when a ‘southerly buster’ ripped through early one morning. One moment Wrapped Coast was a reasonable facsimile of a lunar landscape. The next, the environmentalist in us re-emerged as the plastic sheeting was torn to shreds by the shrieking wind. Nature had reclaimed its own and Christo (consoled by his beautiful wife) was forced to admit defeat.

A windfall for us was the kilometres of polypropylene rope that was there for the taking. Hughie and I dropped the boot lid on my Morris Minor and strapped three 400 metre coils to it. We were part of a team going onto Balls Pyramid in early 1970 and we thought that this rope might prove useful — particularly at the price.

|

Hughie Ward (Left), John Worrall (Right) on the summit of Balls Pyramid in 1970. Hughie is

holding the ubiquitous 'Christo' rope.

(Howard Bevan) |

The rope turned out to be a mixed blessing. For as we took it off the coil to cut it into useful lengths it knotted and twisted into labyrinths of rope that proved difficult to untangle. Some lateral thinking was required and the result was to be the genesis of my recurring nightmare. There are not too many climbers with a 400 metre coil of rope tucked away in the cupboard, but the following might prove instructive on what not to do if you want to cut it into smaller, more manageable lengths. It could also illustrate that simple and seemingly elegant decisions in the climbing world can lead to a lot of trouble.

After a night of deliberation we came up with the following solution to the problem: we were going to make use of geography and gravity to overcome the Gordian Knot. What we decided to do was to take the remaining coils to the Echo Point Lookout at Katoomba and toss them over. Obviously our plan was a bit more complex than that but in our befuddled, inebriated state we had not worked out all of the details.

So on a fine Sunday afternoon we arrived at the car park and struggled down past the bemused tourists with our booty. Placing one of the coils about four metres back from the safety rail I took one end, made a few loops and casually tossed them over the side. Meanwhile Hughie was enjoying the view. The rope slipped gently away, feeding freely from the middle of the coil. This was going to be a breeze. But then the rope began to accelerate. Within about thirty seconds it was leaping out of the coil, arching over our heads and screaming like a banshee as it poured gracefully into the yawning void on the other side of the safety rail. It then occurred to us that apart from not having found the other end, we had also failed to anchor it.

In moments of extreme danger it is a common assumption that the world becomes quiet and that things move in slow motion. However, I can attest that this is only half true. The noise, the speed and the height of the rope increased exponentially as our attempts to find the other end and tie the knot was played out in slow motion. We were still desperately intent on achieving the latter as the coil disappeared.

To this day I do not know who found the end and which of our four fumbling hands somehow secured our booty to the rail. The plummeting aerial cableway came to a halt with an almighty thwump. The slender cantilevered lookout was shaken violently on its foundations. Nearby tourists scattered in fear and trepidation. Hughie and I were lifted off our feet and pulled across the top of the reverberating rail. I can still remember looking directly down the rope to the trees far below as I balanced like a human seesaw on the top of the rail. Hughie had adopted a similar pose and his eyes caught mine as we extricated ourselves from our perch. We both knew that the Grim Reaper had tapped us on the shoulder but had failed to take a swing. With badly bruised hands we climbed back onto the lookout and let the Sounds of Silence do the talking. In the intervening years we have never spoken about the incident but have always acknowledged that we were climbers bonded by a special rope.

Wrapped Coast display in the NSW Art Gallery

for the 50th Anniversary - 2019.

There are many excellent images on the net of the Little Bay Wrapping as well as of climbers working on it. Unfortunately, all of them are subject to copyright.

A2. Tales from the Crypt - Rope Dope

Rock, No 69, Summer (Jan-Mar) 2007, pp. 38-39.

The famous Scottish climber, Tom Patey, did it, along with many others, and I count myself among those who have come close. Bryden Allen nearly did it when he used the handle of his piton hammer as a brake bar, then decided he needed the hammer to get a stubborn nut out — an early example of multi-utilisation perhaps. John Fantini came close high on the south wall of Bungonia Gorge as he abseiled on a double rope, one side which had just been badly damaged in its lower section by stone fall, as did Keith ‘Noddy’ Lockwood while working on a deforestation project below the south lookout of Mount Buffalo. I refer, of course, to dying or injuring yourself while abseiling, rappelling or down-roping and most likely everybody has a story to tell.

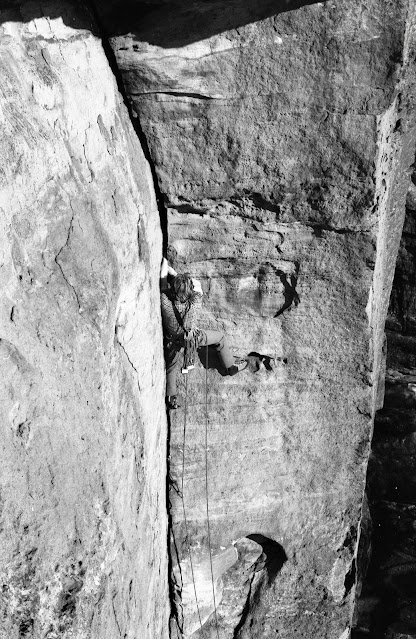

Govetts Leap at Blackheath has a disarmingly apt name for the site of an abseiling fiasco. It is also one of the most scenic lookouts in the Blue Mountains. Straight ahead, beyond Pulpit Rock, the confluence of Govetts Leap Creek and the Grose River can be seen, surrounded by mighty canyons and the rocky bulwarks of Mount Banks. To the right, the silvery stream of Bridal Veil Falls tumbles over a mighty precipice into the valley below, while on the left Horseshoe Fall is hidden by its constricted valley. Between the two, left of Pulpit Rock, is an impressive wall with a rounded top formed by two deeply eroded hanging valleys on either side. The wall is split by a soaring crack reminiscent of Mount Piddington’s The Eternity but almost six times as high and sloping the other way. In May 1970, Howard Bevan and I climbed this crack. We named it Serenity, mocking the trials and tribulations that we encountered, the first of which was access.

|

Directly across from Govetts Leap - Blackheath the abseil started at the creek and landed on the red

orange section. Serenity is the leftward, sloping crack that finishes at the apex of the yellow wall.

|

To get to the base of the crack required descending about 150 metres from the left valley through a small waterfall to a half-way ledge, the abseil hanging free apart from the initial five metres. The government department where I worked kindly donated a coil of 2-inch circumference manila rope for transport to our destination. Top ropes of the ubiquitous ‘Christo’ rope were tied into our swami belts (seat belt waistline) to give an illusion of security (See previous article). The redoubtable Bruce Rowe, affectionately known as ‘Rowetund’ on the Balls Pyramid trip earlier in 1970 was belaying. As wide as he was high, Bruce was a formidable and reliable anchorman.

Howard lost the toss of the double-headed coin and went down first without incident, and all too soon it was my turn. Now this was 1970 and there weren’t any harnesses or sophisticated brake bars: the harnesses we used required stepping into a sling and pulling the section in front of your thighs through the crotch and securing the front and back with a large ‘Stubai’ D-shaped screw-gate carabiner, the braking was provided by a twisted loop or two around the biner’s main stem. We could have also used crossed carabiners or an angle piton clipped as a brake bar across a locking carabiner. While this sounds very primitive they were probably the best systems around at the time.

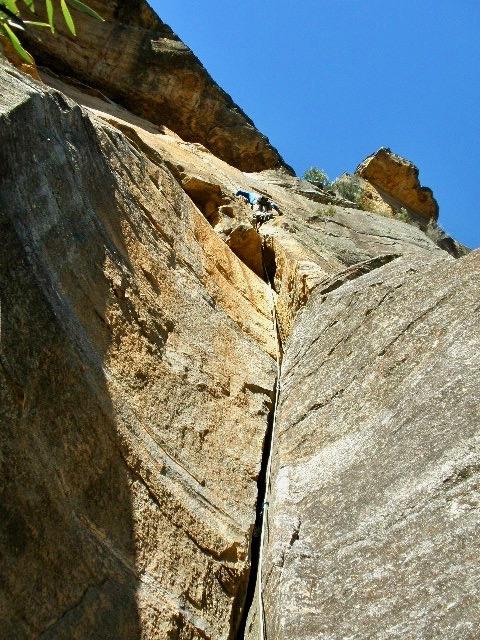

|

Howard Bevan starting the abseil only touching the rock for the first five metres.

The route can be seen bottom right of centre. |

All went well for the first 120 metres until I began coming across the kinks in the rope created by Howard’s descent. The further I went the worse it got. This difficulty was compounded by the size of the rope and the fact that it was now saturated and cold. Very soon I needed all my strength and both hands to push the rope through. As I slowly descended I was getting wetter and wetter and pushing the rope through became harder — before too long I could hang about hands free. Finally, I couldn’t hold myself upright and fell upside down. This was not helped by my much-loved Whillans pack which, although a striking orange colour, was bigger at the top than the bottom and loaded with Peck Crackers, Spuds, MOACS, Ewbank’s nuts as well as Chouinard Bongs, Angles, Lost Arrows and Bugaboos and the odd Leeper — and that was only the climbing gear! It also contained food, water, spare clothes, bivvy gear and was bloody heavy. As a result my sit sling began to ride up my thighs (we’re not talking ‘wedgie’) and any attempt to push the rope through the carabiner just made this worse. Finally the system locked up altogether and I was left dangling upside down on the end of a 120 metre metronome.

It was time to strike up the band and a play a funeral dirge as I gently glided towards the wall, then out over the ledge thus adding an additional 150 metre drop. As I gently swayed across the abyss and back towards the wall my mind wandered as it does when you are just ‘hanging out’. Somewhat crazily, I remembered a Tarzan movie I had seen at a Saturday matinee when I was a kid. The beastly natives had hung Tarzan on a rope by his heels and he was swinging to and fro across a boiling cauldron. I would have preferred this as it was closer to the deck, warmer and did not have the split-level view.

Howard had already changed into dry clothes and was reluctant to move back into the wet zone. Eventually, he realised that I was the proverbial carcass hanging in the butcher’s shop and I wasn’t going anywhere without some external help. Somewhat tardily (my interpretation) he moved back into the line of fire and starting untwisting the rope. After what seemed an eternity I started to make downward progress, albeit still head down. My head finally touched terra firma accompanied by a feeling of relief. This was somewhat short lived – the rocky platform I had landed on was slick and wet with a ski jump shape drop below leading towards the lip of the second drop. Fortunately, further aerobatics/aquanautics were not needed as we made our way out of the creek and across to the start of the climb. It was to take almost two days of free and aid climbing to achieve that end.

Postscript:

In the mid 1980’s I returned with Greg Mortimer and freed the climb in a day. We used an alternative descent that was much shorter and contained less free fall but entailed negotiating a knot, never easy when abseiling. I’m pleased to report that this descent went without incident and also avoided waterfalls.

Incidentally, Bryden Allen managed to hang on in a very steep situation on the upper wall of Janicepts (21) and reinsert the hammer and rope back into place — an early case of climber interruptus?

John Fantini was saved by the fact that both he and his belayer carried hero loops. The latter was able to put a prussik knot on both lines and secure the rope into the belay point before John crossed the damaged area of rope.

Noddy Lockwood had reached my high point on an attempted first ascent at Mount Buffalo and also decided to back off owing to the lack of a bolt or substantial runner. To save leaving gear he looped the rope around two or so ‘trees’ to set up an abseil. Ben Sandilands was on belay at the top of a chimney groove and I was near him on the ledge with a rather slack attachment. The rock above was overhanging and Noddy was out of sight. Suddenly we heard a gasp, and then another. He sounded increasingly worried. Moments later a mass of rope and vegetation came plummeting down with Noddy at its centre. As he whizzed past I stupidly made a grab for the rope and was successful in grabbing something. To my amazement Noddy swung into the chimney groove about 7 metres below like a puppet on a string and stopped relatively unscathed. I didn’t feel any strain and to this day Ben and I (and perhaps Noddy too) cannot satisfactorily explain what happened.

Abseiling is a potentially dangerous activity. From these experiences it can be seen that there are numerous factors that can contribute to your downfall, either singly or in combination. Make sure that you are aware of these, then go ahead and enjoy it or avoid it. I’ll opt for the latter on most occasions.

A3. Start the Ball Game

By the start of 1970, a few climbing goals had been kicked and others had arisen to take their place. In the Warrumbungles, Howard Bevan and I had made the fourth ascent of Lieben, and the first ascent of the Gates of Janus at Mt Boyce. Rather stupidly this ascent was made in the first wear of my first pair of friction boots, a pair of RD’s that featured brown suede leather uppers and bright red laces. The rubber on the sole was case hardened and since it had not been roughed up made the layback up the corner a very slippery affair. The ascent was also cam and hexcentric free leaving the only large protection available, the extruded aluminium hexagonal chunks that were fashioned and sold by John Ewbank.

Balls Pyramid had been climbed in 1965 and again in 1969 and throughout the early months of 1970 this became the focus of our team of six climbers. Many hours were spent collecting, packing and waterproofing food and gear in preparation for our attempt on this amazing tower.

B. HAVING A BALL: 1970, 1973 and 2017

|

| The Western Ridge of Balls Pyramid. |

B1. 1970 Balls Pyramid Expedition Report

Part 1, Thrutch, May/June 1970, pp. 18-20.

Part 2, Thrutch, July/August, 1970, pp. 14-18.

Part 3, Thrutch, Sept/Oct, 1970, pp. 10-11.

First Ascent of the West Ridge of Balls Pyramid near Lord Howe Island in 1970.

Rather than utilize the articles above as they are too long I will use the one in the following publication that is based upon them.

Keith Bell, First Ascent of the West Ridge, Jim Smith and Keith Bell (Eds), South Pacific Pinnacle — The Exploration of Balls Pyramid, Den Fenella Press – 2016, pp. 171-178.

Balls Pyramid is shaped like a huge wafer. Traditionally, the two ridges have always been named according to the direction they point towards. In the past the simple method used was to align the ridges to the north-south axis and the walls to the east and west. However, being the remnant of a volcanic caldera the Pyramid has a banana shape. When placed on a Compass Rose the South Ridge faces southeast but the curve of the Pyramid means that the North Ridge actually faces due west. Both articles use this more recent configuration.

First Ascent of the West Ridge

(Bicentennial Ridge)

Balls Pyramid

11th – 19th March, 1970

The year was 1970 and the Bicentennial of Cook’s discovery of the East Australian Coast was being celebrated. It was at the start of this year that I began my own voyage of discovery, an event that was to resonate throughout my life. The boat, the Lulawai, hailing from Lord Howe Island was approaching a mighty pinnacle of rock rising steeply 560 metres above the ocean. I felt a wave of fear and trepidation, yet tinged with excitement as we neared our destination. Did my companions share these doubts and emotions? Had our dreams and training equipped us for this undertaking?

Balls Pyramid, near Lord Howe Island had been climbed by four members of the Sydney Rockclimbing Club in 1965. I had attended a slide show on this ascent and was determined to make one of my own. Some willing participants emerged: Howard Bevan, Ray Lassman, Keith Royce, Hughie Ward and John Worrall signed up for this venture. Our initial goal was to make a third ascent of the original climb via the SE Ridge, but Bryden Allen, a member of the first ascent team suggested that we should try the unclimbed West Ridge.

A supplied photograph showed a very steep route broken into three distinct sections rising directly out of the sea. This was not going to be a pushover as just landing would present difficulties. Shoals surround the Western End and the boat, unlike at the other end, has to stand some distance out from the rock. We were fortunate that the seas were calm as gear, water and personnel were quickly moved and stored ashore. By sunset of the first day, the 11th March, we were installed about 75 metres above the water in a small grotto-like cave with some small ledges immediately below. The weather was fine and the real climbing would start on the morrow.

|

| The final pitch onto Spinnaker Point in 1970 with wild seas below. (Howard Bevan) |

We were going to siege the climb, which meant that two lead climbers would leave a trail of ropes fixed at intervals behind. This ended at a point just below Pelorus Pinnacle. Rather fortuitously we had polypropylene rope for this purpose kindly ‘donated’ by the avant-garde artist, Christo. The remaining climbers then ascended these ropes with food and water, which were then stored on convenient ledges. Two high camps were established at a Red Cave below ‘Spinnaker Point’ called the ‘Orchestra Pit’ and at the col formed by the same point that was named RIP Ledge owing to a huge obelisk defining its southern boundary like a giant tombstone. By the end of the 15th March fixed ropes had been set up to the base of Pelorus Pinnacle.

I have great memories of my time in what was first called The Red Cave. It was a steep and exposed climb up Oceanview Wall to the sanctuary and safety of this haven. A red arch, cathedral-like roof soared towards the point above giving good protection from the elements. From this vantage point one had a clear view of Lord Howe Island with its twin peaks of Gower and Lidgbird hovering on the horizon. At sunset the shearwaters or mutton-birds would cease their fishing expeditions and land on or near us in a most ungainly fashion as their outspread wings lost lift and they crash-landed onto the ledge. Once settled they would coo softly and this combined with the wash of the waves below reverberated gently through the roof above creating a most soporific, peaceful and musical atmosphere. It was this sound that inspired me to call this bivvy — 'The Orchestra Pit'. These memories are still pleasant, strong and remain with me to this day. (Keith Royce)

The ridge beyond the pinnacle was dominated by the Chichester Gendarmes, a line of thin tottering towers named after the famous aviator who flew his Gypsy Moth seaplane past them in the 1931. The towers were, in places honeycombed with holes or windows, a phenomenon that had been noted by Chichester on his gallant flypast. They were in a word — unclimbable!!! A convenient slot between the Pinnacle and Gendarmes provided access to the northern face, an abseil was set up to gain a vegetated ledge below.

Next day these set ropes provided a quick and easy passage for all to Pelorus Pinnacle and the ledge beyond. A huge traverse along the ledge brought us to the base of the final summit tower. A long pitch up a sinuous unprotected dyke gained a large ledge in line with the top of the Chichester Gendarmes. The team was reunited and a lunch break was called. Above lay the hardest pitches of the climb up a steep and narrow buttress. John and I swung leads up this final section reaching the amazing summit by early afternoon. We left fixed climbing ropes up this section so soon afterwards Ray, Howard and Hughie were able to join us.

|

| Ray Lassman climbing the summit pyramid of the Western Ridge in 1970. (Howard Bevan) |

Rather surprisingly, the summit was flat and spacious and we could move about unroped. A cairn of rocks punctuated its centre and in it we found a bottle with a note on a film packet left by the 1969 second SE Ridge Ascent, which we photographed. In true naval tradition that Cook would have been proud of, somebody had secreted a small bottom of rum in his pack. After each had a tot or two, we renewed the bottle contents with our own note and consigned it to the depths of the cairn. It was the 16th March 1970. The only direction now was down.

Ray left first followed by Howard and Hughie while John and I were ‘tail end Charlies’ tasked with stripping and coiling the fixed ropes. As we went down so the sun also took its inevitable downward path towards the distant sea. We were half way along the traverse when the curtain finally dropped and enveloped us in a velvety blackness. With it came the realisation that we would have to bivouac. We found small cramped ledges about five metres apart, tied ourselves on and settled down for the long night.

No sooner had we done this light rain began to fall. On his tiny perch John was continually being assaulted by one of the Pyramid’s many inhabitants, centipedes. Fortunately, I was not as tasty and came through relatively unscathed. To add to our torment, around two in the morning, a large cruise ship ablaze with lights sailed past. We were immediately assailed with unrequited dreams of a hot cup of tea, shelter and a warm bed. It was a long uncomfortable night.

Dawn broke clear, the rain had passed and John and I continued along the ledge to the abseil line. We quickly ascended this to find Howard had come up the fixed lines on the other side to give us a hand. Long abseils sweeping down the southern face took us back to RIP Ledge where we re-united with Hughie. Howard followed by stripping the fixed lines above the ledge.

Keith and Ray had spent the night in the orchestra pit and headed down the fixed lines to the base camp grotto. They were soon joined by Howard, John and I while Hughie stripped the fixed lines. Once down all hands began to pack the gear into waterproof drums for evacuation and stored them on a small ledge just above the water line. All of the party camped on the Base Camp Grotto and ledges that night.

There was a great deal of excitement on the Grotto Ledge the night before we exited the rock. Some of the group was waiting for the billy to boil when a mutton-bird dropped in for the night. It alighted on the edge of the billy singeing its tail in the near boiling water then squawked, flapped and upset the billy off the burner. The top group desperately tried to save the primus, the billy and the bird but only managed to salvage the former. John, the owner of the billy was too busy laughing to be of any help in any of these matters. The billy and its steaming contents plummeted towards the climbers on the narrow ledge below. They scattered as best they could to avoid either being clonked or scalded and shouted at the top group for their seeming lack of care. The melee finished with the pervading smell of burning feathers and a rather distressed bird flying off into the sunset with smoke issuing from its tail. Everybody fell about laughing, except maybe for John. This was a funny finale to a wonderful trip as this was our last night on the Pyramid. (Ray Lassman)

Next morning on the 19th March, contact was made with the boat at 8.00am as it rounded Mt Gower. The sea was calm enough for evacuation but as this progressed the swell began to break about 20 metres out. Hughie had swum the line out to the boat but the remainder on shore would have to contend with these changed conditions. It was a tough swim to the boat but we were motivated by thoughts of certain triangular shaped fins cutting through the waves towards us. Soon we were all on board, Clive the skipper did a circumnavigation of the Pyramid then headed towards Lord Howe Island. We had successfully completed the first ascent of the Western or ‘Bicentennial Ridge’ of Balls Pyramid.

B2. Balls Pyramid — 1973

Summit, vol. 20, no. 4, May 1974, pp. 2-5.

Reprinted in Jim Perrin (Ed), Mirrors in the Cliffs, Diadem Books London, 1983, pp. 141-145.

First skyline traverse and alpine style ascent of Balls Pyramid in 1973.

Balls Pyramid lies fifteen miles from Lord Howe Island, and is approximately 420 miles northeast of Sydney, Australia. Rising 1,860 feet out of the Pacific Ocean, it is shaped like a wafer, three quarters of a mile long by quarter of a mile wide at the widest point.

The Pyramid was first climbed in 1965 via the southeast ridge. A second ascent of this ridge was made in 1969, followed by the first ascent of the west ridge in 1970. An attempt on the southern face took place in 1971, the team reaching an altitude of almost a thousand feet before a retreat was sounded. All these ascents were sieged. The following is an account of the first alpine-style ascent.

A sense of isolation engulfed me as the boat disappeared behind the edge of the pinnacle. Memories flooded back as I gazed at the lonely sea. Three years before I had stood on the summit of Balls Pyramid, one of a party of six who had pioneered a new route up the west ridge. Now I had returned with Greg Mortimer to attempt the first skyline traverse and alpine-style of the Pyramid. We intended to climb the southeast ridge to the summit and then descend the west ridge. I had planned to do the traverse in 1972, but postponed the attempt owing to an extraordinary amount of cyclonic activity.

Balls Pyramid has unique approach problem. There are no bays, inlets or beaches to facilitate landings; bare rock rises sheer from the sea. The boat approaches as close to the Pyramid as the swell and shoals will allow. It is up to the climbers to swim to the rock and climb to safety above the level of the swell. Previous expeditions had members put out of action before they landed. We landed twice — on the western end to cache supplies and on the southeast end to begin the climb. Fortunately, both landings were on the sheltered side of the Pyramid and the sea was like a millpond. The windward side was a different story; fifteen foot waves were smashing against the rocks.

|

Greg Mortimer on the front cover of Ascent and low on the SE Ridge of the Pyramid.

The landing platform can be seen below.

|

By one o’clock Monday afternoon, February 26th, we had finished the preliminaries and began the long climb up the ridge to the summit. Nightfall saw us safely positioned in an incut horizontal fault a thousand feet above the ocean. The weather that day was fine and sunny with a strong northeasterly wind. Overnight it deteriorated and we awoke to find leaden skies. Towering above was one of the SE ridge’s major features, Winklesteins Steeple. Alternating leads, we were soon moving into the slot between the twin towers of the steeple. Some horizontal ridge climbing was encountered during which we were subjected to an unpleasant buffeting by the wind. The next major obstacle, the Pillar of Porteous, was followed by the Cheval Ridge that lead to the final summit tower. Some hard and exposed climbing was covered as the Pyramid threw down its final challenge.

At 3:30, Tuesday, we were standing atop Australia’s remotest summit, the greatest prize for an Australian climber: a ten-square-metre patch of real estate that barely a score of people had trodden. It felt good to be back. Little had changed in the intervening years. Lord Howe Island, now in view, straddled the horizon to the north, its two major peaks, Gower and Lidgbird rising a thousand metres out of the sea. We found the rum bottle left by the 1970 expedition, and added our jottings to the enclosed note, finishing with a confident, “and now attempting to descend the west ridge”. If we looked confident, we certainly did not feel it.

|

The author on the summit of Balls Pyramid. (Greg Mortimer)

|

Two airy rappels were made from the summit

. I felt like a spider on a string hanging from a fine thread 1,800 feet above the sea. Some roped scrambling followed to a series of terraces. On the end of these terraces and out on the northern face we found a large, comfortable cave, a fortunate discovery as it was 5:00 pm and the weather was threatening. For the first time since landing we were able to contact Lord Howe Island by radio, only to be told that a cyclone was moving south from Queensland.

A comfortable night was spent, protected from the wind and rain by the large, arching roof of the cave. The advance of the cyclone was heralded by low-lying mist and intermittent rain. The wind had ceased blowing in gusts and bore in at a constant velocity, fetching great waves before it. These waves smashed with frightening ferocity against the base of the rock. Our contact advised us to sit tight until the cyclone had passed, but our food and water were running low. Two long rappels took us from the cave to the start of the traverse along the northern face. Four roped pitches along ledges poised above a 1,500 foot drop to the sea, led to the base of a crack system. It was raining heavily and the rock was running with sheets of water. I started up an incipient crack, bridging on minute slippery holds to a point where the crack opened up. I jammed my hand deeply into it, my first secure hold in thirty feet. One hundred feet above Greg, I came to a good ledge and set up a belay. Greg joined me. Shaking with apprehension I moved up the crack until it petered out into a bulge. I pulled out over it the top barely feet away. My eyes wandered down to the sea 1,600 feet below; fear welled up inside me. Suddenly I had it: reach for the loose looking flake and friction with my boots. The key was turned, the ridge was reached and the traverse was almost ours.

Dropping down and traversing under a huge gendarme, we then broke out onto a knife-edged ridge. It was an eerie sensation to sit astride the Pyramid with 1,500 foot voids on either side. Certainly it was no place to linger. A minute later we were off the ridge preparing to rappel. As we swung down past all the familiar places, my mind moved back three years, reliving the moments I had shared with five others on the very same ground. The weather had been fairer then, warm and slightly overcast; perfect conditions for climbing. No cyclones, no wet clothes and shivering bodies; just the sensations of a pleasant, enjoyable climb.

Suddenly I was jolted back into reality as Greg landed on the ledge beside me. Now only 350 feet above the sea we tried to retrieve the ropes. We heaved and pulled to no avail — the rope was securely jammed. Greg jumared up and soon disappeared over an overhang sixty feet above me. Minutes later the rope moved, but his descent brought another problem. Under the overhang he touched some loose flakes, causing a barrage of rocks to come hurtling towards my ledge. I braced myself as they clattered around. A stab of pain shot through my leg as a rock the size of a fist crashed into my knee.

Two agonizing rappels followed to reach the 1970 base camp ledge. It was a relief to get there, as my leg was collapsing under any applied weight. Up and twenty-five foot left was a small cave, our home for the next three days. We retrieved our ropes, climbed up to it, and collapsed, the rigours of the day having fatigued us both mentally and physically.

It was 5:30 pm Wednesday, February 28th. Already a gloom had settled over the sea. Two hundred feet below us the sea was a seething, turbulent white mass. Waves were crashing in from all directions sending froth and foam radiating out into a 500-yard circle. Right before our eyes, birds were plucked from their perches to be pushed before the wind, their wings useless appendages of their bodies. They were gathered up by the sea and drowned. Only the graceful gannets had the necessary strength to ride out the wind. The wafer shape of the Pyramid divided the wind into two streams of differing velocities. These collided violently just yards in front of us and created a vortex three hundred feet wide that zoomed up the face. We had a grandstand view of the awesome power of the cyclone. Never before had I seen such a release of natural energy.

Darkness came and clothed the drama in inky blackness. We prepared ourselves for the long ordeal of the night. Over saturated clothes we placed our waterproof vests and pants, then slipped into large plastic bags, scant protection against the rigours of the storm. Knowledge of the fact that our cached food and sleeping bags lay below us did little to humour us. As the night progressed, the storm intensified. The mouth of the cave was the lip of a waterfall. On nearby Lord Howe Island roofs were torn off houses and palm trees flattened. Many people had their sleep disturbed by the violence of Cyclone Kirsty that night.

Dawn filtered through an oppressive mist and we again resumed our grandstand view of the fight below. We felt heartened by the weak light that now enveloped us. The night had passed slowly. It was the worst bivouac that I had sat through in Australia and certainly the equivalent of the one I had previously experienced on the Walker Spur. It was Greg’s third bivouac, all of which had been on the Pyramid. At least he had probably had his best and worst on the one trip.

|

The shelter cave used to sit out the cyclone,

sitting room for two with two packs. (Howard Bevan) |

By 10:30 am as the clouds scudded overhead patches of blue began to appear. By 12:30 the sky was almost clear, though a trace of wind remained. Thirty minutes later, I was sitting sunning myself on the ledges below. One could scarcely believe that there had been a cyclone. I was looking across brilliant blue water towards Lord Howe Island basking under a clear sky.

Late Friday morning an island fishing boat appeared, but it was too rough to attempt an evacuation. The afternoon passed in dejected silence. Whereas before we had been fighting wet and cold, the sun bore into our cave, broiling us in a natural oven.

Midday Saturday another fishing boat came into sight. We had no choice — lack of food and water meant that we would have to swim for it. We packed our gear and ferried it down to the stowage ledge. Our confrontation with the surf at the lower level was frightening. Huge fifteen foot waves were breaking thirty-five yards out from the rock. Getting our equipment off was out of the question; we would have difficulties enough without the added problem of valuable gear.

The boat stood about 130 yards out just beyond the shoals. Greg and I stood on a platform with the surf boiling around our legs, waiting for a calm moment. When I dived at a wave’s high point, the water level suddenly dropped revealing a mosaic of rock and water. Miraculously I landed in water, surfacing only when I could not hold my breath any longer. Continued diving to avoid crashing waves left me exhausted but the thought of sharks spurred me on. At last the boat, only yards away! With my last ounce of energy I dragged myself to its side, where friendly hands hauled me to safety. Greg arrived and was lifted aboard in the same fashion. We both lay on the deck of the boat like gasping fish, too exhausted to speak. The boat turned and we headed towards Lord Howe Island.

B3. Australian Museum Balls Pyramid Expedition — 2017

Expedition Leader: Paul Flemons, Other Support Staff: Frank Koehler, Hank Bower, and Kate Pearce, Photographer: Tom Bannigan

|

Base Camp - 2017

(L to R) Dave Gray, Tom Bannigan, Hank Bower and Paul Flemons (Expedition leader)

(Courtesy of the Australian Museum - Sydney)

|

Climbing member of this expedition were Zane Priebbenow, Paul Priebbenow, Vanessa Wills, David Gray and Brian Mattick. All climbers reached the summit.

Climbed SE Ridge undertaking a survey for Phasmids and other insects for the Australian Museum, Sydney. 17 Phasmids were found on the ridge and other invertebrates were also collected. A single Phasmid, ’Vanessa’ was transported back to the Melbourne Zoo for breeding purposes. Some new species of invertebrates from those collected have since been identified.

|

On top of that amazing summit again. (Brian Mattick)

(Courtesy of the Australian Museum - Sydney) |

C. ALPINE ANTICS: 1970 — 1971:

|

On the NNE ridge of the Aig. L'm. The Aig. de la Republique is the tower top left

with the Charmoz-Grepon on the right. (Cherie Bremer-Kamp) |

C1. Flying High

It was a Sunday afternoon in either May or early June 1970 when I flew out of Sydney on my first trip to Europe via the classic Kangaroo Route. I had purchased a Jetsetter fare for $390 one way, my wage at that time was probably $60.00 a fortnight. It cost about $1.50 to fill the petrol tank of my Morris Minor when I went climbing. I was running late and when I got to the departure counter there were about five or six airline employees hurrying me up by hollering, “Come on passenger”. This struck me as rather weird.

The reason for their concern soon became apparent as I boarded the plane — I was their only passenger! This was back in the day of the Ten Pound Poms and chartered aircraft returned whether they had passengers or not. I was the only one who had booked on the returning Boeing 707. I had the run of the plane. I played cards with the aircrew and certainly didn’t suffer from a scarcity of drink, food and service. Somewhere over Queensland the Captain called me up to the cockpit. As I was sitting there he asked me if I had seen the big hole at Mt Isa. When the answer was in the negative he motioned me to sit at the right hand window. He then started twirling a little knob and the plane started to tilt. It was finally flying with its wings pointing vertically. “Can you see it?” the pilot asked. “I can see it”, I replied as my face was plastered into a side window by gravity and looking down 30,000 feet into the mouth of a yawning hole. As we were approaching Singapore, the Chief Steward gently informed me that other passengers would be joining the flight and that I would need to act as a passenger rather than an additional member of the aircrew. Point taken. There were about thirty passengers on board when we reached Heathrow.

The other shock to the system was when we reached Bahrain for a transit stop to re-fuel. As I walked down the air stairs from the aircraft there was a guard on either side at the bottom both cradling automatic weapons. This was not something that occurred in Australia or other parts of the world at the time. However, nowadays it is commonplace and there is no doubt that people appreciate their presence.

I’m pleased to report that I made an immediate impact on climbers in the UK. I was climbing with Wilbur King in the Lakes District and it was a typical wet, cold, rainy day. We retreated to the climbers’ haunt, namely the Salutation Hotel in Ambleside, and it was packed. After a few ‘pints of bitter’, Wilbur and I were invited to throw a few darts in a corner of the hotel where a lively competition was taking place. I hadn’t thrown any arrows for years and the pub was so packed there was only an aisle the width of the dartboard for the passage of the darts. On my first throw this was suddenly widened substantially to about four metres and I thought that I might get a bill for the chipped plaster. Bloody colonials!!!

|

Ashes and Diamonds

Swanage on the Dorset Coast. (Rick Jamieson)

|

And so after such an auspicious start with the ‘Games Climbers Play’ I was left to wonder if I could actually make it on the British and European rock that we back in Australia had read so much about.

C2. Chamonix I

To get to Chamonix in 1970, I flew from London to Geneva arriving mid afternoon on a beautiful sunny day. I have memories of walking along a causeway with the lake to my left and once out of the city I started hitching. Almost immediately, Rene, a French climber, picked me up. He was going directly to Chamonix to meet up with some of his friends for a few days’ climbing. They belonged to a club that had a rundown stone building in the town centre and he said that I could stay there the night. Next morning he said he would take me to Snell’s Field where the mainly British contingent camped. Later that afternoon we crossed the Arve River and walked up into the forest on the Aiguilles side to meet up with his friends who were camping. On the way up I remember seeing a brightly coloured adder in the pine needles, the only snake that I saw in France. Rene’s friends did not speak English but they immediately broke out some alcohol that they called ‘The Spirit of the Mountains’. When it came my turn I lifted the bottle high to a horrified “non, non, non”. Too late, the burning sensation was intense; the white spirit was obviously high octane.

Next morning Rene dropped me at the campground and I set up my tent beside twins Alan and Adrian Burgess, very experienced alpine climbers. They were very helpful in many respects. The first thing I needed to attend to after shelter was something to eat. They pointed me towards the local supermarket a kilometre or two down the road in town. I eventually found it and one of the things that I searched the shelves for was oats or porridge. At the time back home this was probably the staple breakfast, a product of our British heritage I guess. But after combing the shelves I could not find it anywhere.

Eventually I saw the manager went up and asked him where I could find this particular item. He took a pace back then looked at me in absolute derision and disdain and declared: ‘Only Englishmen and horses eat oats!!!’ He then stomped off. I considered myself well and truly told and made my way to the fridge for some yoghurt and cheese followed by a baguette. It seemed like I also had a target indelibly printed on me, which was distinctly English. I came to see why the British were held in so much contempt in this part of France.

Later when buying my French cruisine at the supermarket, there was a pair of Scots with large Duvets on and a full trolley. As I passed them later the trolley contained only a few items and presumably the rest had been disposed of back on the shelves or maybe into those voluminous duvets. There were plenty of impecunious climbers in this burg. But most things were reasonably cheap. Alcohol for example, namely Vin Blanc, Vin Rouge (Vin Rough) and ‘pasteurized’ beer cost about 90 centimes a bottle. It could also be refrigerated at the back of the campsite in the Arveyron River that flowed directly out of the Mer de Glace. Buying fruit and veg was always a bit of a hoot, as the young serving girls did not or pretended not to speak English. Ordering and buying things at this counter was always hilarious.

One of the rituals in town was to check out the curbside Meteorological Station for oranges (*) and the height of the 0 degrees isotherm. On the way there several Patisseries were passed with their amazing displays of French pastries. It was sad to window shop and see these amazing morsels sitting so tantalizingly close but walled off by a sheet of glass and French people inside buying up with gusto. Another ritual adopted was to once a week buy two of these treats, retreat to the nearby park, and take tiny nibbles to prolong the ecstasy of these expensive but delicious trifles.

The French had also revalued their currency so there were crappy old aluminium Franc pieces still floating around. These were always given to you as change but when you tried to buy something with them the shopkeepers would not accept them. As time went by a pile of these useless coins was amassed. Rather than keep them a group of co-conspirators came up with a great idea to alleviate us of their presence. A bunch of us lined up alongside the Arveyron and tossed our accumulated aluminium into its tumbling waters. It gave us all a strange sense of power to be reasonably destitute and to disabuse ourselves of seemingly once valued coinage. Perhaps one day it would also provide a treasure trove of artefacts for archeologists?

At one stage an Aussie touring couple camped near me on the field. It was great to have some home company. They had the obligatory Kombi with a kangaroo emblazoned on the front. We went downtown in it and split up to do some shopping. I got back first and since it was a really sunny day rested against the front of the wagon and took in the view of the aiguilles, always rather eye catching. An old Frenchman wobbled past on his bicycle, turned around saw the kangaroo and then me. He swayed to a halt on the curb got off his bike, ran back and gave me a big hug saying, ‘Ohh Australien.’ Having done that he jumped back on his bike and rode off. It seems Australians were OK as long as they didn’t appear British, a difficult thing to do at the start of the 1970’s and without some suitable embellishment.

There were some times I even got to climb when the scarcity of fine weather and climbing partners could be overcome.

(*) Orange = Orage (Fr) = Thunderstorm (Eng)

C3. And Then There Were Two!! - An Alpine Initiation??

In 1970 I was the lone Australian climber in Chamonix. Unfortunately, Mountain magazine had just printed an article by John Ewbank describing his climb on the Totem Pole. This then was the yardstick by which I would be judged. ‘Have you climbed the Totem Pole?’ prospective climbing partners would ask. ‘No’, next moment I was speaking to somebody’s back. It did not seem to matter that the Totem Pole was over a 1,000 kilometres south of Sydney with its own particular access problems. Being an Australian coming from a reputably flat, dry, featureless country did not seem to attract too many good and reliable climbing partners in this town. Finally, I met up with ‘Binks’, a Brit climber of unknown quality given his name. Our first climb was to be the East ‘Mer de Glace’ Face of the Grepon — a long but easier Chamonix classic.

Our aim was to climb to a tiny refuge on the Tour Rouge pedestal, bivouac there, and then complete the climb the next day. All went well: Binks was a solid climber and superb Chamonix granite grooves led up to our small tin shelter situated to the right of the main route. On reaching it we found it occupied by three Japanese climbers. However, their English was good and they didn’t mind sharing the cramped, but comfortable quarters. They told us that they had travelled to Chamonix via the Trans Siberian Railway.

The morning was a hive of activity as we all ate, packed and contemplated the route ahead. The dreaded Knubel Crack lay some seven hundred metres ahead of us, the last bastion to be breached before attaining the summit and its protective Madonna. The Japanese indicated that they were going to solo back along the traverse line to rejoin the main route, and then rope up. I was puzzled by this decision but put it down to peculiar cultural practices. Maybe, it was just a simple ploy to grab the lead on the route?

From the ledge there was about a three metre climb down to the traverse line. The first Japanese started down with a heavily laden pack. He suddenly slipped but landed upright on the ledge defining the start of the traverse. Momentarily, he teetered, but his heavy pack continued to drag him backwards. To my astonishment he went cartwheeling into space. We all stood there in silence — mesmerised.

It took several minutes for us to regain our composure. A rescue or more likely recovery was required and we thought ‘Alpine Ethics’ dictated that Binks and I should take part. The Japanese set up abseils and we went down with them. Their companion had fallen into the bergschrund and was out of sight. They set up an ice axe belay and one of them descended into the bowels of the slot. A voice called out from below, ‘He deader.’

|

Highway to many of the climbs in Chamonix - the Mer de Glace.

Montenvers can be seen ahead, the terminus of the rack railway.

|

The Japanese remained on the snow at the base of the climb while Binks and I trudged back down the snowfield to the nearby Envers Hut. We informed the warden what had happened and he relayed the information onto the helicopter rescue service. He then made us a cup of welcoming tea. About forty minutes later we heard the sound of a chopper and then watched it head for and land where we had left the Japanese at the base of the climb. About ten minutes later it flew off leaving an empty expanse of snow. Binks and I looked at each: we had a long trudge back to Montenvers then down to our campsite in the valley. We had experienced a deadly introduction to alpine climbing with an oriental twist.

C4. All Quiet on the Southern Front or The Storming of the Midi

Not to be dissuaded by this tragedy, Binks and I teamed up again. This time we decided to head for the classic one-day route; the South Face of the Aiguille du Midi, first climbed by

Gaston Rebuffet and Maurice Baquet in July 1956

We caught an early ‘phrique’, plodded across the razor sharp icy ridge atop the Frendo Spur, dropped down right into the Vallee Blanche, then trudged across the snow to the start of climb. We arrived about 7:30 am to be presented with a worrisome sight. It was not the famous S crack that hovered menacingly above that worried us, but the hordes of German alpine troops that festooned the route. What’s more, there were others in ‘foxholes’ at the base of the cliff waiting to climb.

We sat down on the snow and waited, waited and then waited some more. By hell or high water we were not going to allow another Axis country to spoil our climb, particularly given that the return fare to the top of the Midi brought a lot of yoghurt, baguettes, cheese and vin rough. Unbelievably, a bit after midday one of the Germans above started playing of all things, a piano accordion. My patience at this stage was somewhat strained and I shouted up, ‘If you don’t stop playing and start climbing I’ll shove that bloody thing up where the sun doesn’t shine!!!’ Suddenly, silence reigned again across the Vallee Blanche, it seems my invocation had been instrumental in achieving this at least.

|

The storming of the Midi. The famous S crack can be made out between the two Germans

above the lower left overhang. |

Around 1:30 pm Binks and I began to climb. The S crack was clear by this time but when I reached the ledges above they were packed with occupying German troops. In a quick discussion we cooked up a strategy to break through the log jam. It was decided that I would lead with minimal protection and move past the occupied ledges to belay in the crack or groove above. This would effectively block the route and give us the lead on the next section. I would then bring Binks up to the ledge to belay with the Germans. The tactic could then be repeated. It worked wonders and we were making remarkable progress passing the hordes of reluctant soldiers and moving up the route.

At last, a rightward sloping groove led to a shoulder, which seemed to be the end of the climb. As I was nearing the end of the groove a jackbooted German officer with a luger in hand stepped across in front of me barring the way. Well, he was an officer at least and he uttered a rather firm and guttural, ‘Nein!!!’ I glanced across at the wall on my right, it was steep and unprotected but I reckoned it would go. Anyway, my blood was up. ‘Bugger you’, I thought and launched up the wall. The officers mouth gaped as I gained the shoulder, belayed and brought Binks up.

It got messy again. A short abseil was required into a couloir that then led up to the main gallery of the Midi station. However, the system that the Germans had set up to protect it was slow and laborious and we were again caught behind another platoon. At the bottom, I organized the ropes so that the Germans could move quickly and efficiently. Suddenly, Colonel Klink appeared on the skyline and abruptly ordered his men to resume their former time-consuming system. By this time I was really pissed off and just led the couloir until I reached rock. Just above lay an off-take tunnel from the Midi station. It was large, sheltered and expended warm air. I tied off the rope for Binks as he had decided to foster Anglo-German relations. He had probably spent too much time with them in the trenches?

|

| The Midi Station and cableway from the Chamonix side. (Tryfon Kar -Wikipedia) |

The tunnel was very welcoming. I took out some food and water to make up for the deficit of the day. Outside the light was fading fast and a storm was threatening. Soon it was dark, snow had started to fall, the wind had come up, and down below there was a kaleidoscope of flashing torches and occasionally, people could be heard shouting. It looked like mayhem and it was. Hours later a stream of tired, disheveled Germans began moving past my warm bunker up into the galleries of the Midi. Towards the end Binks was one of their number.

We were trapped for the night at the top of the Midi and were quartered in some dormitories set aside for workers. The storm intensified with thunder, lightning and heavy snow. One could almost perish just walking across the small, darkened bridge that connected the two summit pinnacles. Periodically, there was a thick stream of blue sparks flashing along the wires attached to the ceilings of the gloomy galleries and a mighty ‘baroom!’ as lightning struck the ‘rocket’ on top of the Midi. It was a fascinating place to be in such conditions.

Next morning, the thunderstorms had dissipated but heavy snow accompanied by a violent wind still whipped around our citadel. The powers-that-be had decided to run one phrique for the day to get rid on their resident ‘guests’. At the appointed hour we all packed into the cabin. As it moved from the station it was grabbed by the wind and tossed violently in every direction. From above, the ice and snow that had built up overnight on the cable fell in heavy lumps to smash against the top of the cabin with loud metallic bangs. Our climb of the Midi had been a wild ride in so many respects. But then the day before had been traditionally a day of unrest in France; it was Bastille Day. In keeping with the traditions of the day, the Midi had been well and truly stormed.

C5. The Thin Red Line

Thrutch, Vol 50, March/April 1971, pp. 19–20.

See also Wilber King, The Gnome and the Giant, Thrutch, vol. 5, no. 9, January/February 1971, pp. 13-14.

First Australian Ascent of the Gervasutti Pillar on the Mt Blanc du Tacul, Chamonix, 1970.

Standing on the summit of the Auguille du Moine taking in the breath-taking panoramic scene, I let my sight linger on the huge, white bulk of Mt Blanc. There on a subsidiary summit, I saw it, a pillar, a thin red line of rock. I was fascinated by it, the perfect line, straight as a die, but alas climbing partners were difficult to find. I returned to the valley but the thought of climbing the pillar plagued me.

Day after day of good weather slipped by and I was still in the valley. Then one day, as luck would have it, I met an Englishman (Gnommie) with the same fixation (*). He had seen the pillar from the Grande Jorasses the year before and was also entranced by the fineness of its line.

That’s how it started, however, let me fully explain. The mountain was the Mt Blanc du Tacul, northeastern face. The action and the climb involved: an Anglo-Australian attempt on the Gervasutti Pillar. The following events took place over a period of 24 hours.

It began early one afternoon at the Chamonix Telepherique Station. We stepped aboard the aerial cableway to be whisked away on the most frightening ride I have ever experienced particularly on its upper stage. ‘Instant Altitude’ they call it. Frightening? Well yes, but it sure beats walking. Towards the top of the Auguille du Midi the tension was broken by some bright Frenchman’s comment — ‘C’est le chamois.’ He had spotted some climbers steps on the snow ridge of the nearby Frendo Spur.

Once at the Midi all that remained, so I was told, was an easy 15 minute stroll to our illegal bivouac. Unfortunately, Gnommie forgot to tell me about the traverse from the Midi along the top of the Frendo Spur. He bounced off merrily down its sharp, compact ridge leaving me to my own devices. Staggering from conveniently placed snow poles to the next I made my haphazard way repeating to myself, ‘Fall left, fall left.’ The honour of making the first Australian descent of the 3,000 foot Frendo Spur into the Bar Nationale was something I could do without. Finally I arrived at the Col du Midi where the track descends right into the Vallee Blanche.

The hut was reached and after struggling through a mass of cogs, machinery and wire we finally found the cupboard where we would sleep for the night. After some food and many brews we settled down for the night. Meanwhile outside snow had begun to fall and the harbingers of an approaching storm began to illuminate the sky with celestial fireworks. As it got closer the switchboard and machinery at our feet also started emitting blue sparks as the telepherique wire it operated, collected and discharged electricity from above. Fortunately it moved on before our feet were scorched or burnt.

Early next morning at 3:30 am we set off moving by torchlight roped together across the snowy expanse of the Vallee Blanche. The scenery was incredible: to the right stood the Tacul guarding the approach to Mt Blanc; leftward stretched the ragged outlines of the Auguilles; while the Gros Rognon, the Geant and the lofty Grande Jorasses, resplendent in the moonlight towered in front of us.

By daybreak we had negotiated the approach snow slopes and a small couloir to the start of the climb. Gnommie led the first pitch, climbing 100 feet up a leftward diagonal crack to the centre of the pillar. The route then led up a shallow groove, stepped left across a smooth wall to a ledge and continued for 20 feet up a layback crack. At its top another leftward traverse brought us to an easier zone of rock. Several hundred feet of Grade III to IV climbing was covered trending rightward to the steep central section of the Pillar. A start was made by an 80 foot groove which required a traverse left at the top to the centre of the Pillar. From here a crack led up to a small roof before a fairly large ledge was reached at the foot of a spectacular yellow tower. After a short rest it was my lead.

The severity of the climbing brought me back to my senses. After shaking 30 feet up a crack, I went too high past a peg and almost fell down before I could back down. Once at the peg, a delicate rising traverse led to the right hand side of the Pillar. Hard sustained climbing up its edge led directly to the top of the step. While setting up a belay I happened to glance across at the Boccalatte Pillar. On it and level with me were Bob and Pete, two congenial Yorkshiremen. They had started the Gervasutti Pillar the day before, however, so something must have gone astray. ‘What climb are you on Bob, the Gervalatte Pillar?’ ‘No’, came the stern reply, ‘the Boccasutti Pillar, you great Australian git!!’

|

Pete can be seen high on the left of the Boccalatte Pillar in red,

Bob's white helmet can be seen on the ridge in the bottom right third of the photo. |

After much shouting between the parties interrupted by avalanches tumbling down between the two pillars, I was out in front leading up an easy 100 foot groove to the start of the first aid section. This consisted of a short pegged up crack finishing on a large ledge. My lead again. I climbed a groove for 20 feet then traversed left and dropped down slightly over a small bulge into a chimney. The chimney was followed for about 30 feet before friction forced me to belay on some small holds. Gnommie led through up a narrow crest to a small col where 200 feet of strenuous jamming finally attained a large terrace.

Another crack led to the short, difficult second aid section, 20 feet higher up, a 450 foot rising traverse over steep, mixed ground led to the top of the final step. ‘Gnome’ led out three full pitches up this ramp to gain entry to a 60-foot crack leading to a col behind the step. It was on this ramp I nearly came to grief when a snow slope I was standing on collapsed. Fortunately, I had two good handholds and was able to continue dragging my heavyweight frame up the ramp cursing all lightweight, short-arsed climbers.

Once in the col, things began to deteriorate, namely my condition (too much Bar Nat and not enough climbing). We also found ourselves looking at the silver linings within the clouds, while snowflakes drifted gently past us. Gnommie traversed left past two towers and descended 30 feet down the left hand side of the second tower. A descending traverse to the left around the wall of a gully led to an 80 foot chimney ascending to a col formed by a now visible third tower. Once the col was gained we were on easy broken ground where we could safely move together. Several hundred feet later we found our route blocked by a huge red tower. A wide chimney split the middle of the tower and almost instinctively ‘Gritstone Gnommie’ forced a route up it — an off route. Some time was wasted at the top of the chimney traversing to and fro trying to find the route. Finally, I saw some ‘Chamois’ tracks on easy ground about 100 feet below in a couloir. We set up an abseil and descended diagonally to the tracks below.

The ropes came down without a hitch and within minutes we were off moving together over some loose tot. Further deterioration of the weather and a clap of thunder made us halt in our tracks. ‘Will we bivouac or risk going on?’ ‘Bugger it’, came the reply, ‘lets go on.’ The thought of our warm cupboard that night was too appealing.

On we progressed, moving quickly over the broken ground, not sparing a thought for the falling snow and the occasional clap of thunder. Our path trended leftward across the couloir, then up more tottering blocks to a yellow arête. The climbing on the arete became more difficult, perhaps grade III with patches of IV, but our confidence was such that we continued moving together. The rock and the situation were superb. The last 40 feet up the arête to the top of the tower (the large red tower mentioned previously) were very hard, requiring belays. Beyond the tower the climbing changed into classical easy-angled ridge climbing. The weather cleared and all worries about being caught on an exposed summit by an electrical storm were dispelled. Very soon the rock gave way to snow and all that remained was 150 feet of steep snow to the summit of the Tacul.

|

On the Valle Blanche with the Gervasutti Pillar behind

just left of centre in photo. (KBC) |

We kicked our way up the snow slope carefully doing a British ‘Kangchenjunga’ trick by skirting the summit so as to not make the gods angry. A lightning bolt at this stage would make for heated debate. Continuing on we traversed a sharp snow ridge connecting the two summits of the Tacul, skirted it on the right then found tracks leading down a broad snow ridge. On following them they gradually diverged to the right from the ridge proper until we were descending a steep snow slope. Mist again enveloped us and the track suddenly plunged over a precipice into the murk below. Not knowing the runout of the slope we backtracked to another set of tracks that branched out to the right. These traversed gradually back onto the ridge where we found of all things — an igloo. Though it was very well constructed it was not somewhere that we wanted to spend the night. Donning crampons we ploughed on back down the slope from the frozen shelter.

Before we had gone too far, the mist suddenly lifted and the route down the snowslopes to the Col du Midi was now visible. The route threaded its way through numerous crevasses and negotiated many very steep patches of snow. Over to our left the Arve Valley was full of thick cloud and with the sun setting behind the Brevent, it made a truly spectacular sight.